THE DORDOGNE INTERNATIONAL JAZZ SUMMER SCHOOL 2024

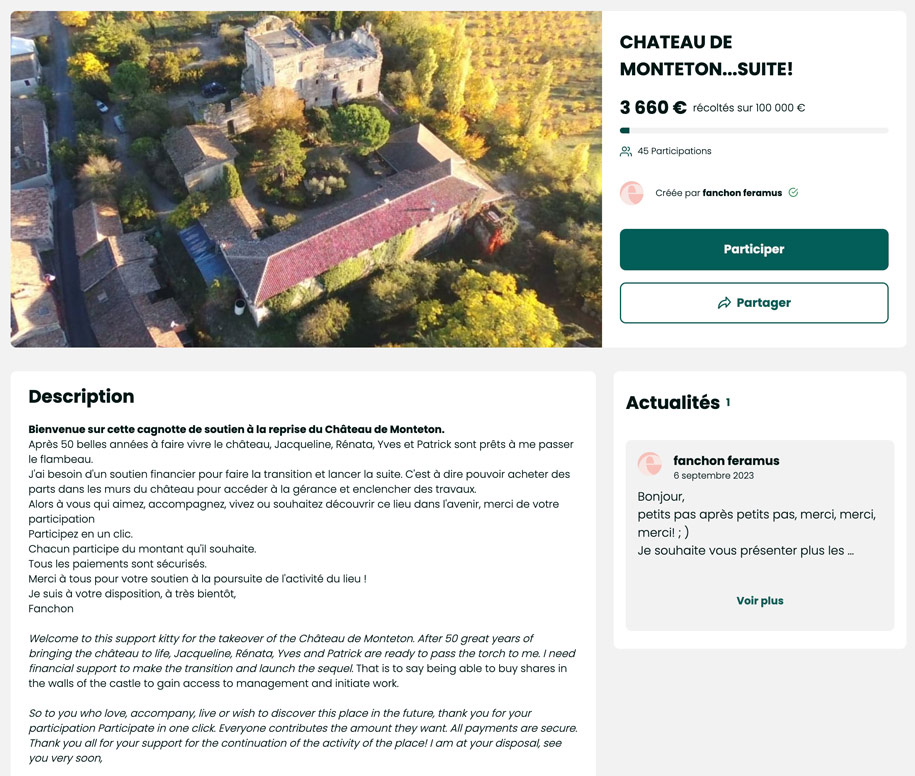

In the family for 50 years, the castle and the inn of Monteton are ready to change hands. Meeting with Fanchon Feramus, who was born there and wants to take over the project. A music studio is installed there, young people came there for Rock and Comics courses, Noir Désir recorded an album there (before the Marie Trintignant murder affair)... it is not the Star Academy castle whose it is, but indeed the castle of Monteton, in the Lot-et-Garonne. Fifty years ago, it was taken over by two couples of friends. Today one of the girls, Fanchon Feramus, wants to continue their crazy project.

“I was born and grew up here,” says Fanchon, at one of the tables in the castle inn. In August 2023, she hopes to buy it back. In 1974, her parents, Patrick and Jacqueline Feramus-Babel, as well as Yves and Renata Dijol-Zamparo were executives and wanted to give up everything. When they bought it, four of them, the castle had probably been uninhabited for two centuries. It's a beautiful ruin. “They cleared the land, and little by little, they made it a place to live,” explains Fanchon. Today, half a century later, they are over 70 years old, and ready to hand over the reins. We could sell to developers or a large hotel group, and let our old days slide, but we want to pass on, and show that this place and its economy are possible.

Patrick Feramus “We avoided selling it, so that this economy could continue. It’s a precarious place, but very rich because of the people who pass through,” adds the founder. “The château has lived in cycles, without really any down period,” explains Fanchon. Quickly, the inn became a table d’hôte. First of all, she has personal development courses. “We welcomed retreats for large groups, but also people who questioned their work. Often, they had given everything and reached a saturation threshold,” says Patrick Feramus. These people had “a desire to recreate a link with a place, even a ruin. It was a somewhat modern monastery.

“We were taken for a sect, for hippies” remembers Patrick Feramus. Ahead of their time, perhaps, personal development was viewed with apprehension. Vegetarian or yoga courses followed.

Then the castle became a mecca for music. In the 1980s, residencies for artists and music groups began. “It was a substantial development of activity at the time,” continues Fanchon. Then around ten years focused on young people, with youth and sport approval. “Each couple had four children. We all grew up together, but in two very separate families. For 10 years, there were stays for young people aged 13 to 17, notably Rock and Comics with Vacances Musicales Sans Frontières (VMSF). » At this time, part of the castle was brought into conformity. These stays ended in 1999. And then comes the return to the artists’ residence, the passage of many groups, notably Noir Désir. “When I passed my baccalaureate, they recorded an album at home,” remembers Fanchon. At the beginning of the century, many weddings were celebrated on the estate, which required a lot of energy from the owners. Then comes the music as the master of the place: courses in jazz, choir, Argentine tango, but also go players. The London jazz school, the International Jazz Summer School, has brought in 70 people since 2003.

After leaving for several years, and having set up a few businesses, Fanchon Feramus wants to take over. “I always knew I would come back, since I was a kid I wanted to take over.” The other children headed towards often artistic careers, like Manu, his brother. Drummer, used to touring, he currently rents part of the castle where he has set up his recording studio.

Returning two years ago, Fanchon Feramus continued in the tradition of the two couples. “I want to allow them to take their foot off the gas. Continue to live here, and enjoy, but without the worries of exploitation. They have spent their lives here, it must continue as peacefully as possible.” And she is full of ideas for business development. But to do this, she needs to “get one foot in the game,” she explains. First by buying shares in the SARL, the operating company, then in the SCI, owner of the premises. And to develop the activity decently, it will above all be necessary to bring the castle up to standard. “This castle lives thanks to good will, but everything is made of odds and ends” underlines Fanchon with a laugh, “Our parents did everything, little by little, with the means at hand”. Some parts are not accessible because they are too dangerous. Others are not well insulated. Or the water takes a very long time to heat up in some bathrooms. "I want to bring it into line, and well," she underlines. That is to say by highlighting the historical heritage of the castle. Part of the foundations date from the 12th century. There is typical Romanesque art from the same period as the village church. “But all this has a cost…

By taking over the activity of the castle, Fanchon Feramus hopes to “sustain and develop the activity”, and “bring the building up to standard”. But above all, he needs a financial contribution in order to buy shares "from the old ones" and to go to the banks. "If I already have a little cash, it will serve as leverage with banks to obtain loans." It is difficult to quantify the expected kitty. A few tens of thousands of euros, at least. “I expect everything and nothing with this kitty, failure is not trying. I believe in the project, and I will contact those who have passed through the château over the past 50 years.”

https://www.leetchi.com/fr/c/chateau-de-montetonsuite-2040593 | ||

|

||

|

||

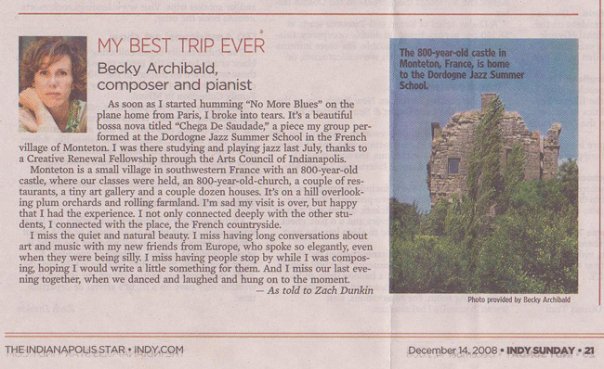

About a year and a half ago, in the winter of 2004-5, I did

a web search for "jazz summer school" and up came

the Dordogne jazz summer school, run by English musicians in

a dilapidated medieval castle in a hamlet called Monteton in

the rural countryside near Bergerac. It sounded very attractive,

and I had some correspondence with the director, but I didn't

manage to get well enough organized to sign up that winter.

The following year I resolved to do it, and by December I had

reserved a place. I made plane reservations in the early spring

and even thought ahead to reserve a hotel room in Bordeaux for

the days before and after the jazz school. As I geared up mentally

and musically for a week of jazz, the war started here in Israel

– making me rather less enthusiastic for the pleasures of life,

including making music. I was a bit apprehensive and imagined the school would be populated

by ambitious, young, talented musicians, who would be too stuck

up to play with me, or, alternatively, with rank beginners from

whom I could not learn very much. However, I assumed that I

would be playing a lot, and that would be valuable. About a year and a half ago, in the winter of 2004-5, I did

a web search for "jazz summer school" and up came

the Dordogne jazz summer school, run by English musicians in

a dilapidated medieval castle in a hamlet called Monteton in

the rural countryside near Bergerac. It sounded very attractive,

and I had some correspondence with the director, but I didn't

manage to get well enough organized to sign up that winter.

The following year I resolved to do it, and by December I had

reserved a place. I made plane reservations in the early spring

and even thought ahead to reserve a hotel room in Bordeaux for

the days before and after the jazz school. As I geared up mentally

and musically for a week of jazz, the war started here in Israel

– making me rather less enthusiastic for the pleasures of life,

including making music. I was a bit apprehensive and imagined the school would be populated

by ambitious, young, talented musicians, who would be too stuck

up to play with me, or, alternatively, with rank beginners from

whom I could not learn very much. However, I assumed that I

would be playing a lot, and that would be valuable. The trip there was not fun. My flight left Ben-Gurion airport

after midnight on Sunday, July 30 and, I arrived in Charles

De Gaulle airport with an hour or so to get to the Air France

window and get a boarding pass for the connecting flight to

Bordeaux. The line was so long and slow moving that I almost

missed the plane. To top things off, when I got to Bordeaux,

I found that Air France had abandoned my suitcase in Paris. The trip there was not fun. My flight left Ben-Gurion airport

after midnight on Sunday, July 30 and, I arrived in Charles

De Gaulle airport with an hour or so to get to the Air France

window and get a boarding pass for the connecting flight to

Bordeaux. The line was so long and slow moving that I almost

missed the plane. To top things off, when I got to Bordeaux,

I found that Air France had abandoned my suitcase in Paris.My hotel in Bordeaux was very easy go get to from the airport, and the people at the reception desk were pleasant. I had arrived before check-in time, but my room was ready, and they had no objection to my going in and resting for a while. Although I was exhausted, after resting for a while, I went out and spent a very pleasant day in Bordeaux, which is an impressive city, full of grand eighteenth century buildings, next to a very wide river, but with a historic center small enough to walk around easily. Since it was Sunday in the holiday season, there were very few people in the streets. As promised, my suitcase was brought to the hotel in the late afternoon. The people at the hotel said it happened all the time. On Monday morning I packed and then took the long walk from my hotel to the railroad station, because I love wandering around towns, and bought a ticket for the 13:35 train to Bergerac. I slowly made my way back to the hotel and checked out at about eleven. There is a tramway that goes directly from where my hotel was, a big park with the strange name of Quinconces, to the railroad station. I have since discovered that "quinconce" refers to an arrangement like the five on a die or a domino: a square with four dots in the corners and one in the center, which is the way the trees are planted in that park. I had a cup of coffee, got on the tram, and had time to eat a salade niçoise in a decent restaurant across form the station (and to have my first of many glasses of red wine) before my train left. The train to Bergerac goes through wine  country, past places like St. Emilion known for their vintages. Upon arrival in

Bergerac, I followed instructions and crossed the street to

a café to wait to be picked up by Simon, the jazz summer school

driver and trouble-shooter, an English expat who seems to

enjoy life. At the café a tall, balding young man saw that

I was carrying a sax case and figured out that I was also

headed for the school. His name was Christophe, he's a pianist,

and he works half-time in computers and half-time as a volunteer

political activist for a small socialist party in Paris. It

turned out he was our token Frenchman in the course, though

we had a French-speaking Swiss engineer as well.Christophe and I had a beer together, and he called Simon

on his cell phone once he figured out the number from the way

it was printed out on the email I had received – my Hebrew oriented

computer had reversed the order of the numbers. The drive to

Monteton was unexpectedly long, partially because we stopped

at the the small local airport to pick up Mike, another pianist,

but Simon was entertaining, as was Christophe.

I was still uncertain how things would turn

out musically. We pulled into the castle and took out

our luggage, but our rooms weren't ready yet, and we didn't

know whom we'd be rooming with. In fact, no one in charge seemed to be around to deal with us.(*proof that this post hasn't

been censored - Ed*) country, past places like St. Emilion known for their vintages. Upon arrival in

Bergerac, I followed instructions and crossed the street to

a café to wait to be picked up by Simon, the jazz summer school

driver and trouble-shooter, an English expat who seems to

enjoy life. At the café a tall, balding young man saw that

I was carrying a sax case and figured out that I was also

headed for the school. His name was Christophe, he's a pianist,

and he works half-time in computers and half-time as a volunteer

political activist for a small socialist party in Paris. It

turned out he was our token Frenchman in the course, though

we had a French-speaking Swiss engineer as well.Christophe and I had a beer together, and he called Simon

on his cell phone once he figured out the number from the way

it was printed out on the email I had received – my Hebrew oriented

computer had reversed the order of the numbers. The drive to

Monteton was unexpectedly long, partially because we stopped

at the the small local airport to pick up Mike, another pianist,

but Simon was entertaining, as was Christophe.

I was still uncertain how things would turn

out musically. We pulled into the castle and took out

our luggage, but our rooms weren't ready yet, and we didn't

know whom we'd be rooming with. In fact, no one in charge seemed to be around to deal with us.(*proof that this post hasn't

been censored - Ed*)We hung around and chatted, about twenty of us, in a pleasant area between a dilapidated stone tower, a terrace with tables set up for dinner, and a low, nondescript building. After a while, some people gathered at the bandstand and started jamming. There was a British bass player named Rick, with a thatch of graying blond hair, and a drummer. Christophe sat down at the keyboard, and I took out my alto. What the hell, I said to myself, why be bashful? After all, I had paid the airfare and tuition to play. I can't remember what tunes we played, but we hit it off fairly well. Other people took out their horns, and we kept going for quite a while. When you think about it, which I have done a lot, it's rather amazing that people who have never met can start making music almost immediately.  Dorian Lockett, a bass player who, with his wife, Andrea Vicari,

a pianist, run the jazz summer school eventually showed up,

and we were gradually settled in our rooms. Andrea's parents

have a house nearby, and their two children stayed with their

grandparents. Her brother Scott, a drummer, was also around

helping out and playing. Dorian more or less takes care of the

administrative stuff, and Andrea is in charge of the jazz summer

schoolmusical program. I was placed with two other guys in a long,

narrow, extremely basic room, with an adjoining bathroom that

was even more basic. I'm not complaining. The beds were clean

and comfortable, there was hot water for showers, and my roommates

were considerate. I had registered as a vegetarian to avoid

problems with kashrut, and at dinner that was no problem – nor

was it ever. The restaurant staff was extremely thoughtful and

friendly. The food was generally fine, never very ambitious,

but always satisfying, with plenty of salad, as much wine as

you could drink at lunch and supper, and fresh bread home baked

from organic whole wheat flour. They served great cheese after

every meal, of course. There was also a bar where you could

buy coffee, soft-drinks, beer, wine, or whiskey. Dorian Lockett, a bass player who, with his wife, Andrea Vicari,

a pianist, run the jazz summer school eventually showed up,

and we were gradually settled in our rooms. Andrea's parents

have a house nearby, and their two children stayed with their

grandparents. Her brother Scott, a drummer, was also around

helping out and playing. Dorian more or less takes care of the

administrative stuff, and Andrea is in charge of the jazz summer

schoolmusical program. I was placed with two other guys in a long,

narrow, extremely basic room, with an adjoining bathroom that

was even more basic. I'm not complaining. The beds were clean

and comfortable, there was hot water for showers, and my roommates

were considerate. I had registered as a vegetarian to avoid

problems with kashrut, and at dinner that was no problem – nor

was it ever. The restaurant staff was extremely thoughtful and

friendly. The food was generally fine, never very ambitious,

but always satisfying, with plenty of salad, as much wine as

you could drink at lunch and supper, and fresh bread home baked

from organic whole wheat flour. They served great cheese after

every meal, of course. There was also a bar where you could

buy coffee, soft-drinks, beer, wine, or whiskey.Look how far I've gotten, and I've barely begun to describe the musical activities. Dorian sent us a .pdf file before the school began, with the schedule, which I printed out and looked at, but it didn't really mean much to me. On Tuesday morning we started off in earnest, and I began to see how much care had been put into planning things. We were placed in two different groups, which met at different times, of course. One was known as a workshop group – each one had about a quarter of the forty participants, selected by instrument. My group, in memory of the confusion of the first evening, was known as the Bed-Hunters. (Another group was known as the Jazz Worriers – to give you an idea of the humor of the place.) Each workshop group met for two hours or so every morning and prepared a piece for performance that evening. We also had three slightly larger ensembles, a Mingus group, a Soul group, and a Salsa group (which I chose, because I'm pretty weak on Latin rhythms). Those groups prepared performances for the final evening of the school, except for the Salsa group. We played three pieces for dancing at a Salsa evening on Friday. We also had instrumental sessions with the teachers, master-classes, and improvisation lessons. sWe had classes from ten to one and then from four to six, and organized jam sessions and performances till eight, when we had supper. After supper sometimes our teachers played for us, once a French group that was sharing the facilities with us gave a concert, and so on. There were disorganized jam sessions until the wee hours of the morning. I stayed up till one-thirty or so one night, but I didn't get much out of that part of the program.  The jazz summer school had four main teachers: two saxophone

players, Julian Siegel and Ingrid Laubrock; one trumpeter, Chris

Batchelor; and one guitarist, Phil Robson. Andrea worked with

the pianists. They are all fine musicians and excellent teachers.

Chris was especially articulate, and, since he directed the

Salsa band, I was exposed to him a lot. Julian was the first

teacher I was exposed to, in a workshop for the advanced saxophone

players (it was up to us to decide what level was right for

us). He's a tall man with a soft face and a lot of black hair.

He speaks quietly, almost bashfully, and in his class he emphasized

sound production in the lower register of the horn: the most

basic stuff is also the most advanced. That afternoon he also

led my workshop group and taught us the song "Sweet Georgia

Bright" by ear, going over it patiently, phrase by phrase,

chord by chord, till we'd got it. Like all the other teachers,

he was terrifically encouraging, telling us we were doing great

all the time. The jazz summer school had four main teachers: two saxophone

players, Julian Siegel and Ingrid Laubrock; one trumpeter, Chris

Batchelor; and one guitarist, Phil Robson. Andrea worked with

the pianists. They are all fine musicians and excellent teachers.

Chris was especially articulate, and, since he directed the

Salsa band, I was exposed to him a lot. Julian was the first

teacher I was exposed to, in a workshop for the advanced saxophone

players (it was up to us to decide what level was right for

us). He's a tall man with a soft face and a lot of black hair.

He speaks quietly, almost bashfully, and in his class he emphasized

sound production in the lower register of the horn: the most

basic stuff is also the most advanced. That afternoon he also

led my workshop group and taught us the song "Sweet Georgia

Bright" by ear, going over it patiently, phrase by phrase,

chord by chord, till we'd got it. Like all the other teachers,

he was terrifically encouraging, telling us we were doing great

all the time.My biggest obstacle to improvising with assurance is my tendency to get lost in the form (or my fear that I'll get lost). I tend to compensate by gluing myself to the lead-sheet, using my eyes instead of my ears, so it was very useful to me to learn something strictly by ear, without the safety net of written music.  Chris Batchelor, a strong and imaginative trumpet player and

a very articulate teacher, addressed a lot of the musical issues

that concern me at the moment in a way that I could grasp immediately. He led our workshop group the next day and taught us a simple,

amusing New Orleans inspired Bill Frisell piece called "In

Deep," also by ear. He also gave a master class demonstration

that day, about breaking out of the patterns of jazz standards

by changing phrasing, by playing the chord progressions out

of phase, and other fairly technical matters. That mainly drove

home for me how firmly you have to have a piece in your mind,

in order to improvise against the structure and not confuse

yourself. Chris Batchelor, a strong and imaginative trumpet player and

a very articulate teacher, addressed a lot of the musical issues

that concern me at the moment in a way that I could grasp immediately. He led our workshop group the next day and taught us a simple,

amusing New Orleans inspired Bill Frisell piece called "In

Deep," also by ear. He also gave a master class demonstration

that day, about breaking out of the patterns of jazz standards

by changing phrasing, by playing the chord progressions out

of phase, and other fairly technical matters. That mainly drove

home for me how firmly you have to have a piece in your mind,

in order to improvise against the structure and not confuse

yourself.But I don't want to go on about the specific things I learned, things that I want to work on and use now that I'm back home. The main point is that by the end of the week, a lot of us were sounding pretty good, playing confidently with a full tone, and enjoying ourselves. People who had never met had formed ensembles and were playing together nicely. Andrea and her brother Scott supervised the early evening jam sessions and made certain that no one got up on stage and monopolized the action, and the atmosphere among us was uniformly generous. People always applauded your solos, even if you got lost and sounded like shit. What may be surprising is that there are enough people like me, mainly middle-aged amateurs, who are serious about our music to populate a jazz summer school like this. The other thing, of course, is that this was a demonstration that jazz has convincingly become a world music – you don't have to be American or African-American to love it or play it creditably. At our final concert, on Sunday night, August 6, our performance groups played: the Mingus band, the Salsa band, and the Soul band. The Mingus band started off with "Better Get Hit in the Soul," a lively evocation of black evangelical churches. There they were, about twelve white Europeans playing the blackest of black music with enthusiastic respect. And then another twelve northern Europeans played Cuban music with love and abandon. I've always looked at my musical activity, at least in one sense, as something that takes me places – and indeed it has. |

info@jazzschool-dordogne.co.uk mob +44 79 4192 72578

(It was especially

poignant, since earlier in the day he was rushed to the hospital

because of a fall, and didn'tknow if he would be able to use

his hand that evening.) I can hear Irene playing the simple

melody on her flute, and sweetly singing one of the verses.

I've been holding back the tears since Saturday, and they come

easily on the plane sitting by a stranger (a very kind one,

thankfully.) I'm sad it is over, but certainly happy that I

had the experience. I want to see everyone again. I not only

connected deeply with -rightthe other students at the workshop, I

connected with the place, with Montenon, with the French countryside.

I'll miss the owner's friendly face, his beautiful children

who worked behind the counter and played the dice game with

me, and Jean-Baptiste, the man who ran the art gallery nearby.

I'll miss the quietness, the natural beauty, the air, and having

our large windows wide open at night because of the lack of

bugs and humidity. I'll miss being served three splendid meals

a day, watching people saunter in one by one for morning coffee

and cereal, having long conversations about art and music and

anything except what we actually did for a living, and taking

everything at a slow place. I'll miss being with my new friends

from England, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, Austria and France,

who speak so elegantly, even when they are talking about silly

things. I'll miss having people check in on me late at night

while I'm trying to compose music, asking me how it's going,

wanting to hear a few bars, encouraging me to finish, offering

advice on chord changes and titles and styles I should write

in and hoping I'll write a little something for their instrument.

And I will miss our last evening together, after the concert,

when we relaxed and danced to salsa music and laughed and hung

on to the moment.

(It was especially

poignant, since earlier in the day he was rushed to the hospital

because of a fall, and didn'tknow if he would be able to use

his hand that evening.) I can hear Irene playing the simple

melody on her flute, and sweetly singing one of the verses.

I've been holding back the tears since Saturday, and they come

easily on the plane sitting by a stranger (a very kind one,

thankfully.) I'm sad it is over, but certainly happy that I

had the experience. I want to see everyone again. I not only

connected deeply with -rightthe other students at the workshop, I

connected with the place, with Montenon, with the French countryside.

I'll miss the owner's friendly face, his beautiful children

who worked behind the counter and played the dice game with

me, and Jean-Baptiste, the man who ran the art gallery nearby.

I'll miss the quietness, the natural beauty, the air, and having

our large windows wide open at night because of the lack of

bugs and humidity. I'll miss being served three splendid meals

a day, watching people saunter in one by one for morning coffee

and cereal, having long conversations about art and music and

anything except what we actually did for a living, and taking

everything at a slow place. I'll miss being with my new friends

from England, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, Austria and France,

who speak so elegantly, even when they are talking about silly

things. I'll miss having people check in on me late at night

while I'm trying to compose music, asking me how it's going,

wanting to hear a few bars, encouraging me to finish, offering

advice on chord changes and titles and styles I should write

in and hoping I'll write a little something for their instrument.

And I will miss our last evening together, after the concert,

when we relaxed and danced to salsa music and laughed and hung

on to the moment.